[This text is reproduced in its entirety from the following publication: Diane Upright. Morris Louis: The Complete Paintings. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1985, p. 59-62].

Unless otherwise specified, material quoted in this outline is taken from the Morris Louis Archives (see Bibliography no. 1)

|

|

The History of the Written Word (detail). 1934. 3 panels, each about 5 ft. x 20 ft. (152.4 x 609.6 cm). Oil on canvas. Inscribed panel 3, l.l.: Sam Swerdloff assisted by Calvin Hisley, Maurice Bernstein [Morris Louis]. Collection Hampstead Hill School, Baltimore, Maryland. Executed in situ under the auspices of the Public Works of Art Project. |

28 November 1912

Morris Louis Bernstein was born in Baltimore, Maryland. His parents, Louis Bernstein (born 21 October 1877) and Cecelia Luckman Bernstein, had emigrated from Russia. His father was initially a factory worker, but later owned a small grocery store. Louis was the third of four sons; his two elder brothers, Joseph and Aaron, became physicians, and the younger, Nathan, became a pharmacist.

1918–27

Louis attended public schools in Baltimore: No. 11 Primary School (Caroline Street), No. 77 Primary School (Washington Avenue), Gwynns Falls Junior High School, and Baltimore City College.

1927–32

In a state competition that he entered at the age of fifteen, Louis won a four-year scholarship to the Maryland Institute of Fine and Applied Arts. His transcript reveals that he was a slightly better than average student. He was awarded a diploma by the Fine Arts Department in June 1932.

Louis admired the work of Eugene Speicher (1883–1962) and Cézanne, and visited the Cone Collection in Baltimore with his friend Charles Schucker, also an artist, two or three times (interview with the author, 23 June 1978).

1933–36

Louis shared studios in an office building in Baltimore with Schucker and also with Ben Silbert. Louis held a variety of odd jobs to support himself during these years: he peeled vegetables for an Italian restaurant, folded clothes in a laundry, gathered information for the Gallup Poll, mowed grass in a cemetery, and helped his pharmacist brother, Nathan.

|

|

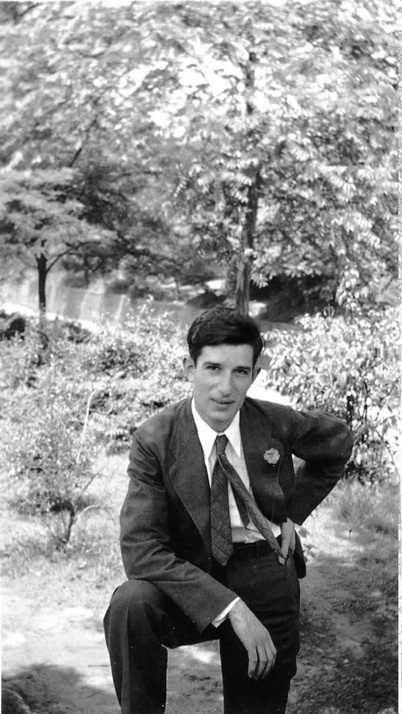

Morris Louis in the late 1930s. |

January–June 1934

Using the name Maurice Bernstein, Louis was one of two assistants who worked under Sam Swerdloff on a mural in Baltimore commissioned by the Public Works of Art Project. Louis’s federal payroll record shows that he was paid $26.50 per week. The mural, titled The History of the Written Word, occupies three 5-by-20-foot panels in the library of the Hampstead Hill School at 101 South Ellwood Street. Louis’s most significant contribution to this collaborative project consisted in research on early forms of writing that appear in panel 1. He also served as the model for the third figure from the left in panel 3. It was not possible to determine which areas or figures he actually painted.

1935

Louis was elected president of the Baltimore Artists’ Union, which was founded in 1934. Its first president, Mervin Jules, had moved to New York.

1936–37

Sometime in 1936 Louis moved to New York. Until he found his own living space, he moved in with Chet LaMore, a friend from Baltimore who was then living on West Twenty-first Street. Louis painted the floor of the apartment in return for LaMore’s hospitality. LaMore recalls that Louis made satirical, figurative line drawings. He described Louis in this period as “very reserved—non-communicative—to the degree which suggests ‘withdrawn’” (letter to the author, 27 August 1978).

A résumé that Louis prepared in 1952 stated that he participated in the Siqueiros Workshop, which opened on West Fourteenth Street in April 1936 and closed early in 1937 after Siqueiros left for Spain. At the workshop artists experimented with new techniques and materials. The projects created there included floats and posters for the May Day parade and antifascist rallies.

Louis supported himself with a part-time job as a window decorator, and he received a small allowance from his family.

He became friendly with the paint manufacturer Leonard Bocour, who ran a small shop on West Fifteenth Street. Bocour gave away small waxed-paper packages of paint that was left over after he filled the tubes for a given batch of color. Louis was just one of many painters who benefited from his generosity.

In March 1937, Louis and a group of painters from Baltimore, including Mervin Jules and Herman Maril, exhibited together at the A.C.A. Gallery on Eighth Street. The exhibition was reviewed by Joseph Solman in Art Front (see Bibliography 3). Solman refers to “Morris Louis,” the first indication in print that Louis had changed his name.

1938–c. 1942

On 27 October 1938 Louis was issued a new Social Security number under his recently adopted name. The card specified that his address was 1362 Sixth Avenue and declared him “unemployed as of 10-27-38.”

Soon thereafter Louis registered with the Works Progress Administration (WPA). His identification card described him as 5 feet 10 inches tall, weighing 138 pounds, with dark brown hair and eyes. Federal payroll records show that Louis was employed by the Easel Division of the Federal Art Project from 27 February 1939 until 27 August 1940 at a salary of $91.10 per month.

During these years Louis lived at 334 East Twenty-fourth Street with a young woman who was an art teacher also employed by the WPA. She has described him as subdued, quiet, and contemplative, disinclined to talk to others unless they were thoughtful people. She recalls that Louis was a member of the Steering Committee of the Easel Project. He painted very regularly, six to eight hours a day, and produced many pictures of workers and scenes of poverty. The artist who most interested him was Max Beckmann; Louis reportedly did many paintings in Beckmann’s style, including a triptych (no trace of which was discovered by the author). Louis was profoundly moved by the Spanish Civil War; he made posters and went to protest meetings. With very little money for anything but essentials, Louis and his companion had little social life, although they enjoyed frequent visits to the Museum of Modern Art, since WPA artists were given free admission to the museum and its film showings (interview with the author, 20 March 1983).

In 1939, Louis exhibited Broken Bridge (cat. no. 5) at the WPA Pavilion of the New York World’s Fair.

1943–47

Louis returned to Baltimore, although the exact date of this move cannot be determined. He was never drafted into military service and was apparently classified 4F. He lived with his parents, relied on financial support from his brothers, and used the family basement for his studio. His widow—then his next-door neighbor—recalls seeing him slouched on a porch chair, a brooding and frustrated man.

1947

Louis married Marcella Siegel on July 4. They moved to her two-room apartment at 8010 Eastern Drive in Silver Spring, Maryland, a suburb of Washington. They converted the bedroom into his studio and used the other room for living, eating, and sleeping.

1948

Louis exhibited a gouache in the “Maryland Artists, 16th Annual Exhibition” at the Baltimore Museum of Art. His work was also included in the “Baltimore National Watercolor Exhibition.”

He began using Magna, an acrylic resin paint manufactured by Leonard Bocour. Magna was the only paint Louis used for the rest of his career.

1949

Louis exhibited in the “Maryland Artists, 17th Annual Exhibition,” whose jury (James Johnson Sweeney, Jack Tworkov, and Jean de Marco) awarded his painting Sub-Marine (cat. no. 16) the “Mrs. Martin Kohn Award of $50.00 for work in any medium.”

1950

At the “Maryland Artists, 18th Annual Exhibition,” the jury (Lee Gatch, Mary Callery, and Carl Zigrosser) awarded Louis’s collage Nest (present location unknown) the “Berkeley T. Rulon Memorial Prize for any medium showing original work in a modern direction.”

Louis served on the Artists’ Committee of the Baltimore Museum in 1950 and in 1952, acting as the Artists’ Equity representative during his second term.

1951

|

|

Wedding portrait of Morris and Marcella Louis, Baltimore, 1947 |

At the request of three painters in Baltimore, Dr. Gus Highstein, Helen Jacobson, and Lila Katzen, Louis commuted to that city once a week to teach them (see Bibliography 258).

1952

Louis and his wife moved into Washington, where they purchased a house at 3833 Legation Street, N.W. Louis converted the 12-by-14-foot dining room into the studio he was to use for the rest of his life.

Jacob Kainen, a Washington artist, helped Louis to obtain a teaching position at the Washington Workshop Center of the Arts, which was founded in 1945 by Leon and Ida Berkowitz. Louis taught two adult painting classes each week. He became friendly with Kenneth Noland, also an instructor at the workshop.

1953

Louis taught a one-semester course at Howard University, and continued teaching private students in Baltimore and Washington in addition to his classes at the Washington Workshop.

Louis and Noland spent the weekend of April 3–5 in New York, where Noland introduced Louis to Clement Greenberg. During the weekend they visited galleries together and saw paintings by Franz Kline and Jackson Pollock, among other artists. They also visited Harry Jackson’s studio. On Saturday evening Louis and Noland, accompanied by Greenberg, Charles Egan, Kline, Margaret Marshall, and Leon and Ida Berkowitz, visited Helen Frankenthaler’s studio. They were especially impressed by her poured stain painting Mountains and Sea (dated 26 October 1952).

On April 12, a week after his return, Louis’s first one-man show opened at the Workshop Art Center Gallery. He exhibited thirteen paintings, three collages, and a group of drawings. Among the works shown were some of the Charred Journal series (cat. nos. 30–36), and the Tranquilities collages (cat. nos. 40–42).

1954

|

|

Morris Louis (left) teaching at the Workshop Center of the Arts, Washington, D.C. The photograph first appeared in the Washington Post, March 13, 1953. |

On January 5, Greenberg visited Louis and Noland in Washington to select work for the exhibition “Emerging Talent” that he was organizing for the Kootz Gallery in New York. He chose three paintings by Louis, Trellis (cat. no. 48), Silver Discs (cat. no. 44), and Foggy Bottom (present location unknown). On January 7, Louis and Noland took the paintings to New York. They met David Smith, Harry Jackson, Frankenthaler, and Greenberg the next day. The show at the Kootz Gallery opened on January 11. Louis and Noland visited New York again on February 6 and saw Frankenthaler and Greenberg.

In Washington, Noland included a painting by Louis in the exhibition “5 Directions” that he organized at Catholic University, where he was teaching. During the spring and summer, Louis exhibited Dark Thrust (cat. no. 49) at the Barnett Aden Gallery.

In June, at Greenberg’s suggestion, Louis sent nine recent paintings to Pierre Matisse in New York. In a letter dated 6 June 1954 to Greenberg concerning these paintings, Louis wrote:

Just finished rolling & wrapping ptgs to go to Matisse. It was the usual struggle with my normal doubts re the stuff continually rising & then concluding that they were, after all, ptgs I’d done & I’d have to let it stand at that this time. I realize I’d gone overboard on the later stuff, none of which you’d seen. By your arrangement with me you’ll get to see them & I want that above all. And this will be the best way to let you know what I’m doing.

There are 9 ptgs in the roll which R’way Express is supposed to come get tomorrow. All are about the same large size but in my mind 2 of them are different than the continuity of simple pattern & slow motion of the majority. These 2 are the rougher ones with lots of black & white areas. Maybe these are lousy enough to interest me now & make me want to explore this further. The others I feel I’ve about done all I feel like doing about that episode. For a moment I looked at “Trellis” & a couple of others you’d seen before. Just couldn’t bring myself to include them & with all the doubts I ever had about anything I’ve ever chosen alone I submit this group.

Matisse was not responsive to Louis’s paintings. They were then taken to Greenberg’s apartment, where they remained for a number of years. In 1958, J. Patrick Lannan bought seven of them (cat. nos. 53–57, 61, 68).

Louis went to New York on December 20 for a three-day trip. He joined Greenberg for visits to the studios of Friedel Dzubas and Willem de Kooning. He also saw Frankenthaler and Harry Jackson.

1955

|

|

Exhibition announcement for the show "Emerging Talent" at the Kootz Gallery, New York, 1954. |

Greenberg visited Louis in Washington on April 2–3. He was not favorably impressed with Louis’s recent work. He encouraged Louis to visit New York more often to understand better the weaknesses of his paintings, which were similar to much work then being exhibited in New York.

In June, Louis was included in a group show at the Workshop Center of the Arts, and in October his second one-man exhibition was held there. Nine paintings were included in the show.

1956

|

|

Morris Louis standing in front of Untitled (cat. no. 76). c. 1956 |

Louis exhibited one painting in January at the Barnett Aden Gallery in Washington.

1957

|

|

Telegram from David Smith to Morris Louis on the occasion of Louis's first one-man show, held at the Martha Jackson Gallery, New York, 1957. |

In May, Louis was included in a group show at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York. Roy M. Neuberger bought a painting from this exhibition (cat. no. 74). Louis visited New York on April 18–19 to stretch the paintings for Castelli.

He went to New York again on September 10–11 and returned once more on November 4–5 to attend the opening of his first one-man show there, which was held at the Martha Jackson Gallery. Greenberg had brought Louis to Jackson’s attention earlier in the year. She visited Louis in Washington in May, accompanied by Michel Tapie de Ceyleran. For the exhibition they selected twelve paintings; among them were the Neuberger painting shown previously at Castelli, one bought by Tapie (cat. no. 76), one now in the collection of the University of Arizona (cat. no. 79), and a Veil painting from 1954 then owned by Greenberg (cat. no. 63). Tapie wrote an introduction for the catalogue (see Bibliography 20). Louis subsequently destroyed nearly all of his paintings from 1955, 1956, and 1957. Only one surviving painting, Longitude (cat. no. 58), bears the date 1955, but Louis’s canvas order receipts for that year indicate that he received 158 yards of canvas. Given the average size of his paintings at that time, he probably destroyed about one hundred paintings made in 1955 and about two hundred more painted in 1956 and 1957.

1958

Louis’s work was included in exhibitions at the Baltimore Museum of Art (cat. no. 75), the Osaka International Festival in Japan (cat. no. 78, a painting selected by Michel Tapie), and in Philadelphia at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (cat. no. 81). Louis had shown this last painting, a large bronze Veil, to Mrs. H. Gates Lloyd in the spring. When she bought it a few months later she told him to send it directly to the exhibition in Philadelphia. It marks Louis’s return to painting Veils, which he had abandoned in 1954. The sale of the painting brought Louis three thousand dollars, the largest amount he had yet received for a single painting. With the money from this and the Lannan purchase of six paintings, which occurred about the same time, Louis had some repairs made to his house and visited his parents, who had moved to Florida.

Louis taught a painting seminar in Baltimore. His students’ work was exhibited in April at the University of Maryland Psychiatric Institute as “Stages in the Creative Process.”

1959

Louis went to New York on March 10–11, in all probability to attend the opening of French & Company’s new Contemporary Department, for which Greenberg served as artistic advisor. Louis had been selected for its second exhibition, but the opening was a one-man show of Barnett Newman’s paintings. The exhibition, which included twenty-nine paintings from 1946 to 1952, was Newman’s first in New York since his show at Betty Parsons Gallery eight years earlier. Louis had already become interested in Newman’s work, which he had seen reproduced in Art News in the summer of 1958. Leonard Bocour recalls that he introduced Louis to Newman at about this time when they all accidentally emerged from taxicabs at the same place. Bocour was surprised to discover the two artists had not met previously because Louis had spoken to him of Newman with admiration and apparent familiarity (interview with the author, 8 March 1972).

Louis’s one-man show opened at French & Company at the beginning of the second week in April, and the artist went to New York for the opening. Greenberg had selected twenty-three Veil paintings for the exhibition, nine painted in 1954 and the rest from 1958. William Rubin was so favorably impressed by Louis’s show that he brought the work to the attention of his brother, the art dealer Lawrence Rubin, who began buying the paintings the following year.

Greenberg also included three of Louis’s Veil paintings in a summer group show at the new gallery.

In Baltimore, in March and April, a second exhibition of the work of Louis’s seminar students was held; the reviews praised Louis as a teacher.

1960

|

|

Exhibition catalogue listing for a one-man show of Morris Louis at French & Company, New York, 1960. |

On March 23 Louis’s second one-man show at French & Company opened. From a list, dated 1 February 1960 (now in the Morris Louis Archives), of forty-seven paintings selected by Louis, Greenberg had chosen twenty-one. Louis made two trips to New York in conjunction with this show: February 29–March 1 and March 21–22.

Greenberg also organized an exhibition of Louis’s paintings for Bennington College in October. In addition, the critic manifested his advocacy of Louis’s work in his essay “Louis and Noland,” which appeared in the May issue of Art International (see Bibliography 34). In the January 1960 issue of the same publication, William Rubin wrote favorably of Louis in his essay “Younger American Painters” (see Bibliography 36).

In May, Louis’s work was exhibited in Paris at the Galerie Neufville, in which Lawrence Rubin was a partner. In September, Louis signed a contract with Rubin permitting the dealer to buy paintings and arrange exhibitions in Europe.

Louis’s paintings were also exhibited in other European cities this year, for the first time: in London at the Institute of Contemporary Art in the spring, in Milan at the Galleria dell’Ariete in November, and in Rome at the Rome-New York Art Foundation in November.

In April Louis received sixteen gallons of a new formula of Magna paint, each of a different color, that Leonard Bocour had mixed especially for Louis and Noland. Bocour mixed the pigment with 50 percent Acryloid F-10 and 50 percent turpentine, eliminating the beeswax binder that had previously been used to keep the pigment in suspension. The new consistency was more fluid, like that of maple syrup, and was far more amenable to Louis’s requirements.

Louis made one other trip to New York, on May 20–21, and in August Greenberg visited him in Washington to see his newest paintings.

French & Company closed its Contemporary Department after the spring exhibition season. Andre Emmerich became Louis’s dealer in the United States.

1961

In a letter to Greenberg dated 26 February 1961, Louis reported with pleasure that, as a result of the sale of paintings to Rubin, he had bought a secondhand Thunderbird. He wrote, “The important thing about the T-bird is the extravagance—something I’d not had a chance to be before.”

Louis’s improved financial condition also permitted him to take advantage of David Smith’s advice about keeping large quantities of materials at hand; although he had only ordered 230 yards of canvas in 1959, his orders had increased to 1,185 yards in 1960, and to 1,245 yards in 1961.

Louis’s visits to New York increased to ten this year. Four trips in September and October were made in conjunction with his first one-man show at the Andre Emmerich Gallery in October. The show at Emmerich consisted of ten Stripe paintings.

Other important exhibitions this year included a one-man show in Paris at the Galerie Neufville, two group shows in London, and the group show “American Abstract Expressionists and Imagists” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, which displayed a Stripe painting.

|

|

Morris and Marcella Louis celebrate her newly awarded Ph.D. in June 1962. |

1962

Louis went to New York once a month from January through May. His April visit was made in conjunction with the opening of Noland’s show at the Andre Emmerich Gallery.

Greenberg visited Louis in Washington in March. Early in April, Emmerich came down to select a group of recent paintings to make available for sale, since nearly all of the paintings from the October 1961 exhibition had been sold.

On July 1 cancer of the lung was diagnosed. Four days later Louis was operated on for removal of the left lung. After a week in the hospital, he began out-patient cobalt ray treatments three times a week. He was never again well enough to paint.

He wrote four letters to Emmerich between July 18 and August 30 discussing his second exhibition at the gallery, which was scheduled for October. His primary concern was that the paintings he selected for the show be stretched properly in his absence, since he realized he would not be well enough to travel to New York to supervise the stretching himself. James Lebron, who had previously stretched and framed Louis’s paintings, came to Washington early in August to discuss the stretching of the eight Stripe paintings Louis had selected for the show. The canvases were marked for stretching, signed, dated and titled, and Lebron took them with him back to New York.

Louis also corresponded with Greenberg during July about his forthcoming show. On July 18 he wrote:

One more thing on the pictures. Before the operation, in June, I did a couple which, if they can be stretched by Lebron as I intend them, should I think make a transition move from the vertical picture I’d done for so long to the big unfurling ones such as used at Bennington. When you come down we’ll unroll these 2 ptgs—I’d like to know what you’ll think about them. I’d like to use them in Oct. show so as to make possible the large unfurling ones next time.

The “unfurling” paintings shown at Bennington are Alpha (cat. no. 335) and Delta (cat. no. 325).

Louis wrote to Leonard Bocour on July 23 and ordered six gallons each of six different Magna colors.

On 7 September 1962, Louis died at home in Washington. He was buried in the Adas Israel Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

The scheduled exhibition opened at the Andre Emmerich Gallery on October 16.

1963

In September, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York opened the exhibition “Morris Louis 1912–1962: A Memorial Exhibition of Paintings from 1954–1960.” Lawrence Alloway selected the sixteen paintings for the show and wrote the catalogue essay.